MOBILITY IN THE CITY

Global Summer School – Manila Node 2020

For centuries, Manila and its neighboring towns and cities have economically prospered through the aid of the trading system within the bodies of water in its surroundings. Some of which are rivers and estuaries defining some cities and barangays’ boundaries. Once known as the Pearl of the Orient because of its reminiscence of European cities with its cobbled streets, European-Tropical architecture and its rich culture and history but in the present century those perceptions are far from the truth.

As decades passed by, Metropolitan Manila, with a land area of 619.60 square kilometers, what used to be a small quaint city has morphed into a beating megatropolis home to approximately thirteen (13) million. Yet with the rapid urbanization also has a cost: Massive migration caused (3) million informal urban settlers weaving all throughout the metro, with its urban density even reaching 42,857 people per square kilometer in the city of Manila whose total area is only about 39 square kilometers including its 140 hectares of available public space.

Given that its current population is about (1,78) million people, this only equates to approximately (0.8) square meters of green space per resident of the city. As the massive demand for housing continues to grow, it has substantially contributed to the cannibalization of the metro’s only available open spaces, leaving people little to none spaces left for socialization and leisure. Not only did it also critically impact the cities’ infrastructure and resources, it also caused an apathetic disconnection with its primary binding force, the rivers and waterways. People started turning its back on it creating a vacuum filled up by the cities’ ISFs (Informal Settler Families) who have also desecrated these spaces turning them into hazardous and unlivable spaces. And so, the question, is there still hope for Manila and its esteros and riverbanks? Is it still possible to fix the Metro’s problem with its fading greenspaces?

Statistics (source: Grey, S. (2017) Resilient Edges: Exploring a Socio-Ecological Urban Design Approach in Metro Manila)

- Philippines among the top three countries at risk of extreme natural disasters according to World Risk Report

- An average of twenty typhoons hit the Philippines yearly.

- Until the latter half of the twentieth century, the vast majority of Filipinos lived in rural areas, but from 1975 to 2010 the population of Metro Manila ballooned from 5 million to nearly 12 million.

- Nearly 3 million informal urban dwellers (600,000 families) live in the metropolis today.

- In 2014, approximately 18% of informal settler families live both without legal claim and in primarily high-risk areas.

- Approximately 6,000 tons of trash goes into waterways, landfills, or streets every day.

- 42% increase of flood impacted areas by 2050, affecting nearly 2.5 million people living in low-lying areas by 2100.

For centuries, Manila and its townships has grown along its rivers and estuaries as it provided its people easy access to life’s necessities yet this has changed especially after the trauma experienced by the Filipino people during the 20th century. From wars to uprisings, this has proven stressful for the city. To satisfy the rapidly growing demand, it became the start of the people’s amnesia towards its symbiotic relations with the city’s waterways.

Manila, being the capital of the Philippines, is rich in history and heritage. From the establishment of Intramuros, to the on-going cultural revitalization of Escolta, Manila’s dynamism has kept the city constantly evolving and growing despite its faced adversities. However as the city continues to grow, the gap between the rich and poor has also significantly widened, creating an unequal distribution of public space. With the population density rapidly increasing now more than ever, space ends up becoming scarce for a necessary demand. This has resulted to the lack of respect and ownership to the city which contributes to the urban decay that the city is now experiencing.

Part of Manila’s distinct features is its esteros or river inlets that weave through different parts of the city. These waterways are a part of Manila’s rich history, from being a platform for transportation and commerce in the early days, shifting to being just merely an inoperative backyard. This change in the dynamics of cityscape has affected its population, especially communities living along the esteros and riverbanks. Esteros no longer function as they used to, overpopulation and the practice of irresponsible garbage dumping are the main culprits to the problem, creating hazardous and unlivable spaces in which these communities are stuck with.

And so, the question, is there still hope for the esteros? What changes can be done to alleviate inhumane living conditions that plague the people of Manila?

Despite the harsh impression imposed by our society, one can never truly know the stories hidden within. For what it may lack on its surface, it is compensated by the heart and soul of the community. Vibrant and full of hope.

Straddling along Estero de Tripa de Gallina, Barangay 739 is a victim of ruthless urbanization and capitalism brought upon by decades of political neglect and exploitation. Despite the hardships, they still continue to adapt and thrive in such harsh conditions, creating a certain mindset along the way. Reinforced by their lack of access to proper information, it has proliferated into obliviousness onto their surroundings specifically along the periphery of their community, further creating a sense of isolation towards the rest of the city.

This is the starting point. Isolation is a hindrance to growth. It creates a disconnection towards its surroundings, man and nature alike, so why not tackle this by proposing a new vision for the residents of Barangay 739 by creating a new space for its people to foster.

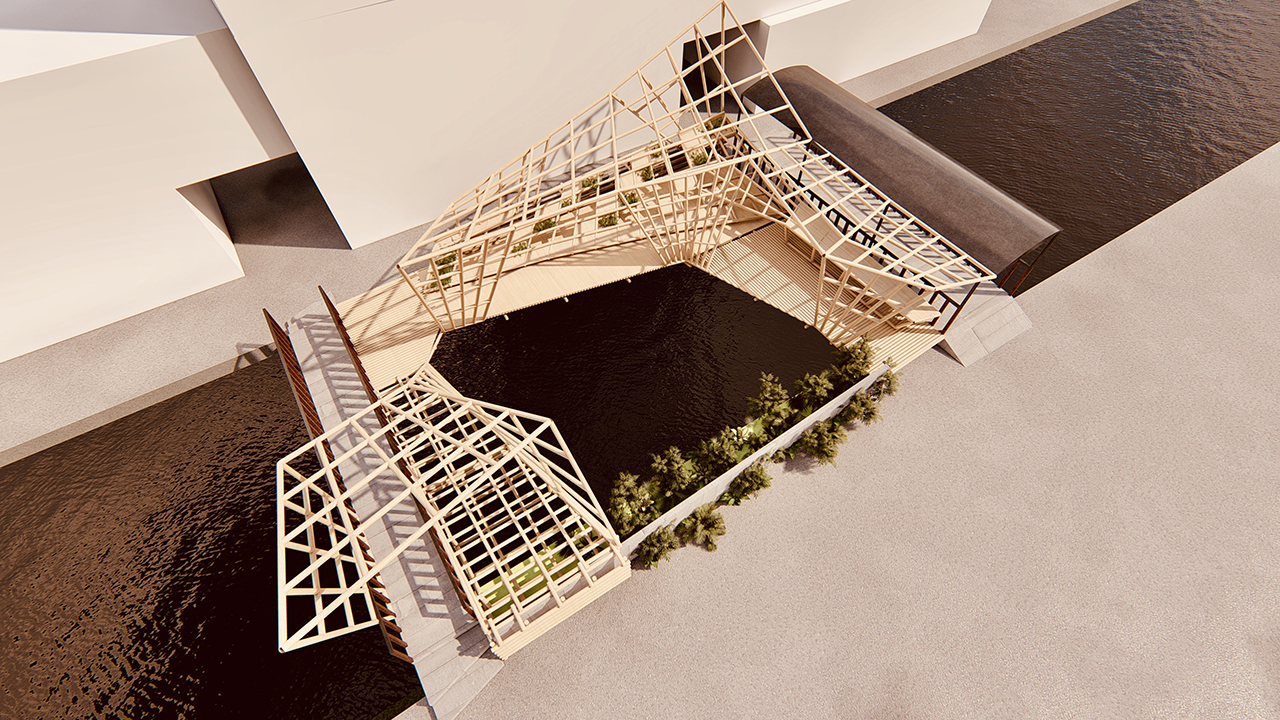

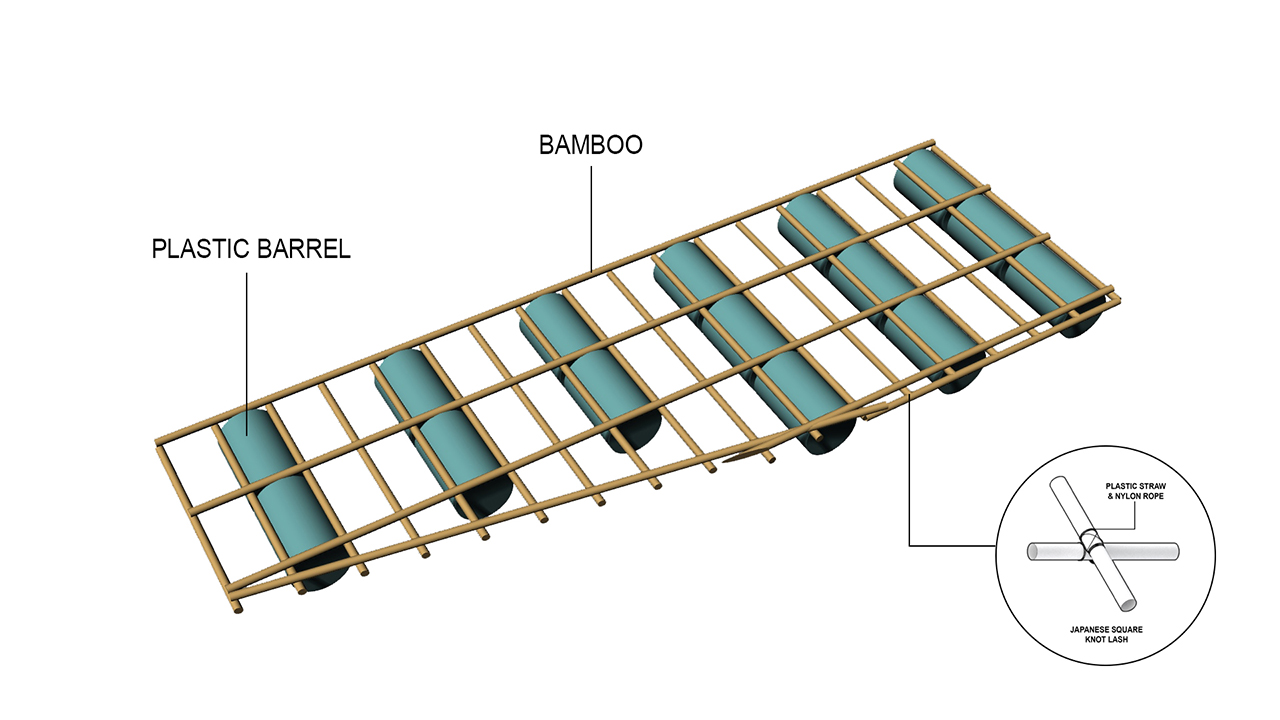

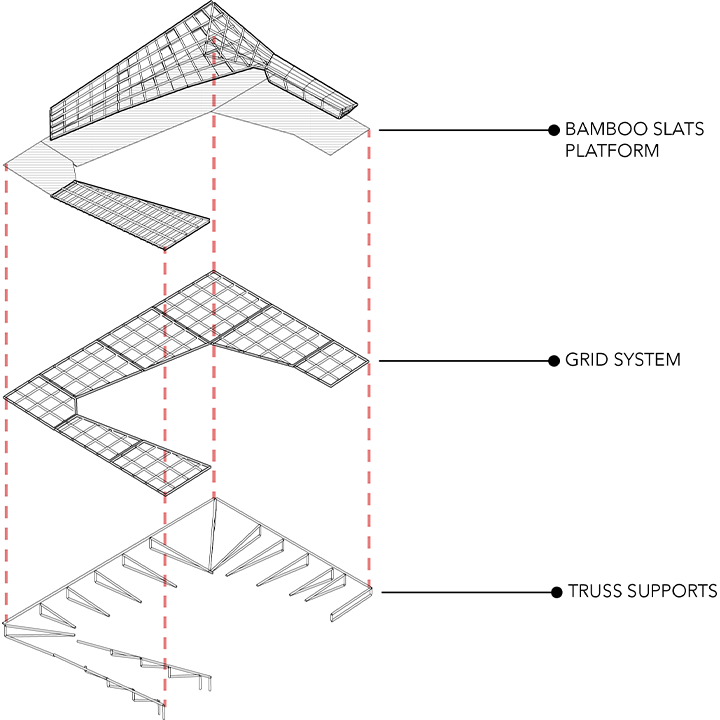

The GSS Node of Manila aims to create a solution to the area’s two main physical problems— lack of public spaces and unsustainable trash management. By creating an extension to their public space, it forms an expansive platform for socialization, but also taking into account the neglected connection, the Estero. In creating an inclusive space, it allows the residents to have a better relation to the water way, which can consequently become a catalyst for proper rehabilitation of not just the estero, but also their behaviour.

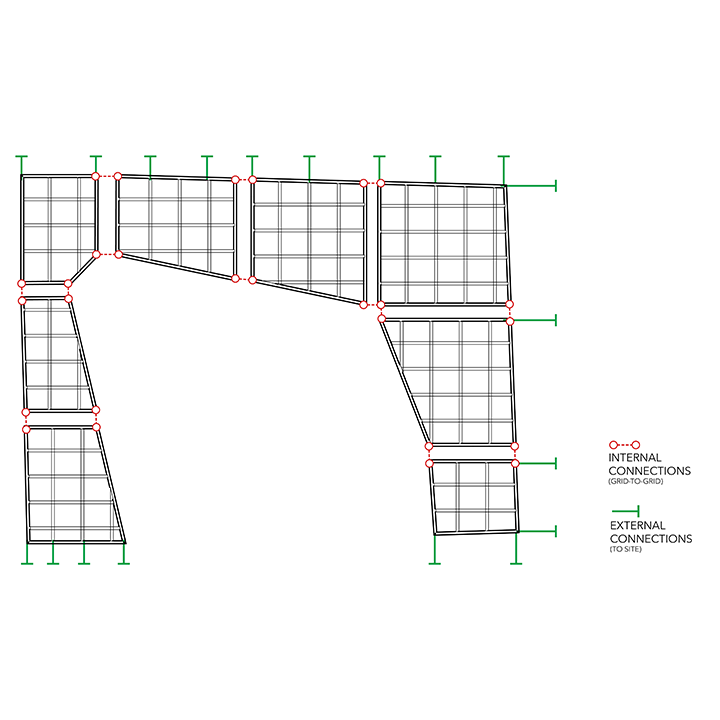

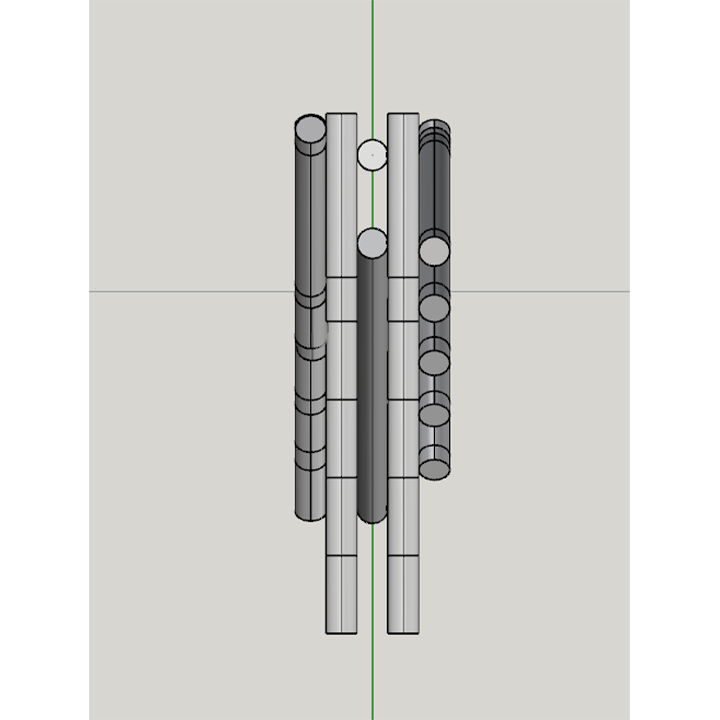

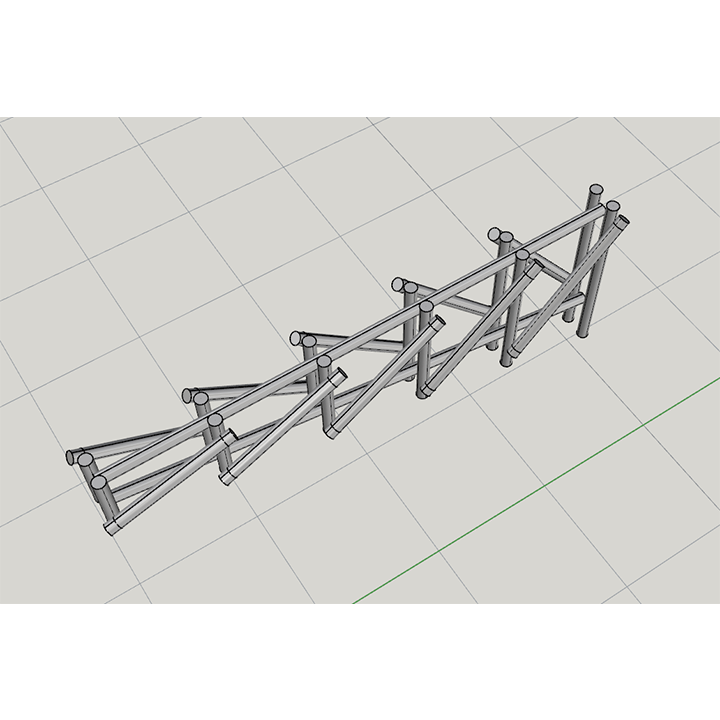

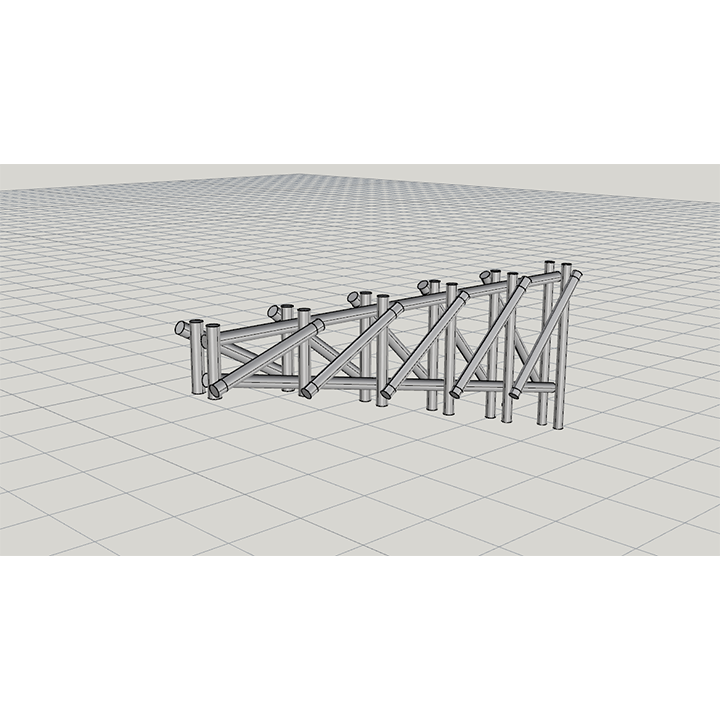

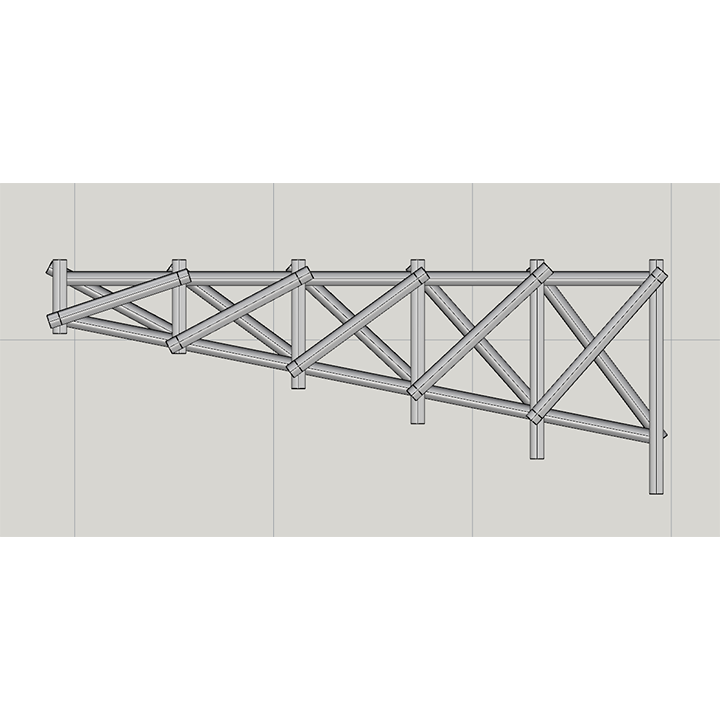

The structure which will be located in between the two main portals into the community from Arellano Avenue is designed in a way that it mimics the current programs of the two bridges and to amplify it into a larger scale. Based on the three main activities seen during the site visit, the structure is divided into three main programs namely: Laro, Kain, and Tambay.

LARO

A space designated for the youths of 739, it is designed in a way that it promotes the use of creativity and imagination to the segment. Given the current restraints, Its main entry is located along the front road. Since there are no sidewalks dividing the Estero and the road, the group has decided on using a ladder system to compensate for the CHB wall located in between. The structure is sloping two-thirds of the span whose elevation starts from the top of the CHB wall which gradually levels along the same grade of the covered bridge’s walkway.

The slope is masked by the use of the typologies: steps and nets. The sloped section is designed with duality in mind, a smooth and a rough path, by playing with the arrangement of the steps and the nets. But of course, no Laro is fun without a surprise. The group has decided to integrate traps throughout the structure, but (shhhh!) detailing more about it would definitely invalidate the surprise.

KAIN

As the saying “Food brings people together” goes, this perfectly encapsulates the Filipino people’s love for food because it acts as a medium for people to socialize and connect to the members of society. This has been deeply engraved into the Filipino culture which is why it is often to see markets and food spaces in almost every wards or districts of the country. Barangay 739 is no different. Despite having a very high density and very little open or empty spaces, the area still boasts a number of Karinderias and Hawkers yet it takes away a vital piece from the district’s residents: Space.

This segment is designed to offer a solution to that problem. Oriented towards some of the community’s various “karinderias” and hawker food stores, the “Kain” component of the pavilion acts as a better alternative to the current conditions faced by the sellers and consumers. By designing it beside the covered bridge, it could act as an extension to the informal food spaces setup on the bridge’s walkway so there’s more reason for people to patron and encourage the growth and prosperity of the local economy.

TAMBAY

The segment patterned from the Filipino’s past-time, Tambay was designed with one thing in mind – as a conducive space for socialization for the members of the community where they are able to share collective experiences or discuss philosophies.

Located on the back side of the estero and facing the road, the Tambay segment not only acts as a bridge between the other two segments, (Laro and Kain,) its is placed in a way that it if has a sloping component wherein it is divided into different segments to afford a variety of uses, so not only can it be used to seat people, the individual panels can be repurposed into small pocket gardens that they can use.